Milk production in India increased from 17 million tons in 1950-51

to 84.6 million tons in 2001-02 and is expected to reach 88 million tons during

2002-03 (GOI, 2003). Therefore, from being a recipient of massive material

support from the World Food Program and European Community in the 1960s, India

has rapidly positioned itself as the world's largest producer of milk. Milk

production in India during the last five decades is shown in Figure 2.1 and

Tables 2.1 and 2.2.

Milk

production in the country was stagnant during the 1950s and 1960s, and annual

production growth was negative in many years. The annual compound growth rate

in milk production during the first decade after independence was about 1.64

percent; during the 1960s, this growth rate declined to 1.15 percent. During

the late 1960s, the Government of India initiated major policy changes in the

dairy sector to achieve self-sufficiency in milk production. Producing milk in

rural areas through producer cooperatives and moving processed milk to urban

demand centers became the cornerstone of government dairy development policy.

This policy initiative gave a boost to dairy development and initiated the

process of establishing the much-needed linkages between rural producers and

urban consumers.

Figure 2.1 Milk production and

consumption trends in India: 1950-51 to 2001-02

Table

2.1 Annual growth rate (%) of production of major livestock products in India.

| Period |

Milk |

Eggs |

Wool |

| 1950-51 to

196-61 |

1.64 |

4.63 |

0.38 |

| 1960-61 to

1973-74 |

1.15 |

7.91 |

0.34 |

| 1973-74 to

1980-81 |

4.51 |

3.79 |

0.77 |

| 1980-81 to

1990-91 |

5.68 |

7.80 |

2.32 |

| 1990-91 to

2000-01 |

4.21 |

4.46 |

2.01 |

| Source: GOI, 2003. |

The performance of the Indian dairy sector during the

past three decades has been very impressive. Milk production grew at an average

annual rate of 4.57 percent during the 1970s, 5.68 percent during the 1980s,

and 4.21 percent during the 1990s. The country's milk production is expected to

reach 84.6 million tons in 2001-02.

Table 2.2 Annual growth rate (%) of milk, eggs, and

wool in India: 1975-76 through 2001-02, by plan

| Plan |

Year |

Milk |

Eggs |

Wool |

| 5th Five Year Plan |

1975-76 to

1979-80 |

2.91 |

3.5 |

1.49 |

| 6th Five Year Plan |

1980-81 to

1984-85 |

6.42 |

8.4 |

2.67 |

| 7th Five Year Plan |

1985-86 to

1989-90 |

4.37 |

7.23 |

1.88 |

| 8th Five Year Plan |

1992-93 to

1996-97 |

4.41 |

4.58 |

0.80 |

| 9th Five Year Plan |

1997-98 to

2001-02 |

4.13 |

4.34 |

2.14 |

Source: GOI, Basic Animal Husbandry Statistics 2002,

Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Ministry of Agriculture.

This growth was achieved through extensive intervention by the

Indian government, as well as through increased demand driven by population

growth, higher incomes, and urbanization (Candler and Kumar, 1998). Until 1991,

the Indian dairy industry was highly regulated and protected. Milk processing

and product manufacturing were mainly restricted to small firms and

cooperatives. High import duties, non-tariff barriers, restrictions on imports

and exports, and stringent licensing provisions provided incentives to

Indian-owned small enterprises and cooperatives to expand production in a

protected market. Indian policy makers saw the development of the dairy sector

as a measure to create supplementary employment and income among the small and

marginal farming households and landless wage earners, as milk production takes

place in millions of rural households scattered across the country.

Despite its being the largest milk producer in the world, India's

per capita availability of milk is one of the lowest in the world, although it

is high by developing country standards. The per capita availability of milk,

which declined during the 1950s and 1960s (from 124 gm per day in 1950-51 to

121 gm in 1973-74) expanded substantially during the 1980s and 1990s and

reached about 226 gm per day in 2001-02 (Figure 2.1). The per capita

consumption of milk and milk products in India is among the highest in Asia.

However, it is still below the world average of 285 gm per day and the minimum

nutritional requirement of 280 gm per day as recommended by the Indian Council

of Medical Research (ICMR).

Several factors have contributed to the increased milk production

in the country. First, milk and dairy products have cultural significance in

the Indian diet. A large portion of the population is lacto-vegetarian, so milk

and dairy products are an important source of protein in the diet. The demand

for milk and dairy products is income elastic, and growth in per capita income

is expected to increase demand for milk and milk products. Empirical evidence

has shown that the composition of an average Indian's food basket is gradually

shifting toward value-added products, including milk and dairy products. The

proportion of income spent on milk and milk products increased from 11.7

percent in rural areas and 14.7 percent in urban areas in 1970-71 to 21.6 and

16.7 percent in 1999-00, respectively (Annex Table 2.1). Other socioeconomic

and demographic factors, such as urbanization and changing food habits and

lifestyles, have also reinforced growth in demand for dairy products. On the

supply side, technological progress in the production and processing sectors,

institutional factors, and infrastructure play an equally important role. The

linking of rural small producers with urban consumers through producers'

cooperatives was a true institutional innovation in the Indian dairy sector.

Given its high income elasticity, the demand for milk and dairy

products is expected to grow rapidly. A study conducted by Saxena (2000) using

National Sample Survey (NSS) data for 1993--94 showed that income elasticity of

demand for milk and milk products is higher (1.96 national level) in rural

areas (ranging from 1.24 in Punjab to 2.92 in Orissa) than in urban areas

(ranging from 0.99 in Punjab to 1.78 in Bihar). The northern region in general

and Gujarat in the western region show low income elasticity of demand for milk

and milk products. The high values of income elasticity for different states in

the eastern region-varying from 2.5 to 2.9 in rural areas and from 1.5 to 1.8

in urban areas-show a very strong preference for milk and milk products with an

increase in income. Further increases in per capita income and changing

consumption patterns would lead to acceleration in demand for milk and other

livestock products in India and thus would give a boost to this sector.

Radhakrishna and Ravi (1994), Gandhi and Mani (1995), Kumar (1998), Dastagiri

(2001), and others have estimated demand and income elasticity of demand for

milk and milk products, and show similar trends (Table 2.3).

Delgado

et al. (2001) have estimated per capita consumption of milk products in

developing countries to be about one-third that of developed countries in 2020;

however, in aggregate terms, 60 percent of world milk consumption will take

place in developing countries, which is a major shift from the early 1990s,

when the developed countries consumed 59 percent of world milk production. The

projected growth rate for milk is expected to be around 4.3 percent during

1993-2020. Kumar (1998) projected demand for milk at 142.7 million tons by 2020

at 5 percent growth in GDP (182.8 million tons at 7 percent growth in GDP). The

estimates given by Saxena (2000) are different than other estimates and project

demand for milk to reach its peak at 85.7 million tons in 2007-08 and decline

thereafter. Saxena argued that the domestic market may expand if a rise in per

capita income is more in favor of lower income groups and regions, as the

income elasticity of demand for such groups and regions (eastern) is much

higher. The wide variations in demand estimates are mainly due to different

assumptions of elasticity, population projections, and other parameters.

Table 2.3 Income/expenditure elasticity of demand and

estimates of demand for milk in India

| Rural |

Urban |

Demand

for milk by 2020 (million tons) |

||||

| Radhakrishna

and Ravi (1992) |

1.15 |

0.99 |

- |

|||

| Gandhi and

Mani (1995) |

1.70 |

1.06 |

- |

|||

| Kumar

(1998) |

- |

- |

126.0-182.8@ |

|||

| Saxena

(2000) |

1.96 |

1.32 |

85.7# |

|||

| Delgado,

et al. (2001) |

- |

- |

132.0 |

|||

| Dastagiri

(2001) |

1.36 |

1.07 |

147.21 | |||

Notes: @:estimates

based on 4% growth in GDP (126.0), 5% growth (142.7), and 7% growth (182.8); #:

estimates for 2007-08.

2.1.1

Regional Patterns of Growth

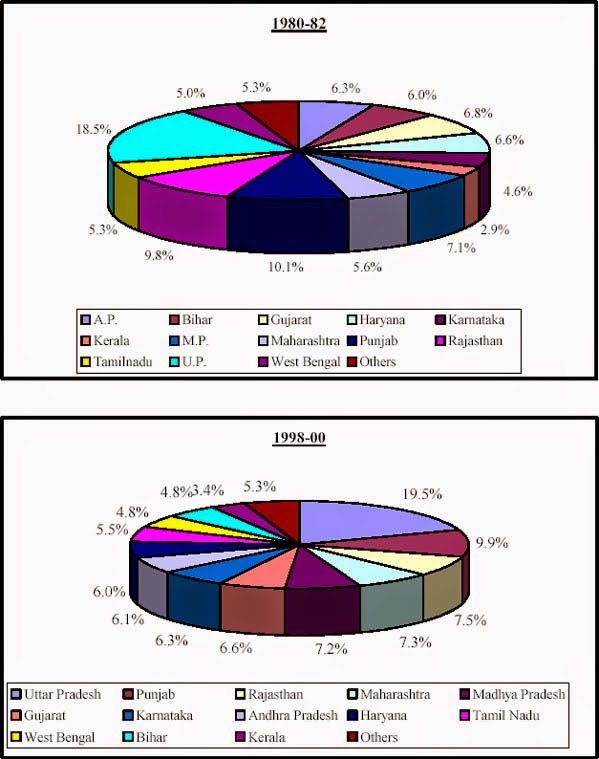

There are large interregional and interstate variations in milk

production as well as in per capita availability in India. About two-thirds of

national milk production comes from Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Madhya

Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, and Haryana. However, there have

been some shifts in milk production shares of different states. In 2001-02,

Uttar Pradesh was the largest milk producer in the country with about 16.5 million

tons of milk, followed by Punjab (8.4 million tons), Rajasthan (6.3 million

tons), Madhya Pradesh (6.1 million tones), Maharashtra (6 million tons), and

Gujarat (5.6 million tons) (Annex Table 2.2). During 1982-83 triennium ending

(TE), the top five milk-producing states were Uttar Pradesh (18.5%), Punjab

(10.1%), Rajasthan (9.8%), Gujarat (6.8%), and Haryana (6.6%). During TE

2001-02, Uttar Pradesh (19.5%), Punjab (9.9%), Rajasthan (7.5%), Maharashtra

(7.3%), Madhya Pradesh (7.2%), and Gujarat (6.6%) were the largest producers.

The share of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Punjab,

Uttar Pradesh, and Orissa increased between 1991 and 1999-01, while the share

of Bihar, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal

declined. The regional shares of milk production are presented in Figure 2.2.

Major milk-producing regions in the country have good resource endowment and

infrastructure. The eastern region is lagging behind in terms of dairy

development. The government has initiated various dairy development programs,

especially for the eastern and hilly regions.

There are also wide variations in per capita availability of milk in the country. The per capita availability of milk in major states and union territories is given in Annex Table 2.3. The average per capita availability is lowest in the eastern region and highest in the northern region (see Figure 2.3). The average per capita availability of milk during 2000-01 was highest in Punjab (997 gm/day), followed by Haryana (645 gm), Himachal Pradesh (354 gm), Rajasthan (300 gm), and Gujarat (296 gram). Only 10 states had higher than the national average per capita availability of milk (220 gram/day). The per capita availability is low in the eastern and northeastern states. Milk production and per capita availability in major states during TE 1998-00 are presented in Figure 2.4. The average per capita consumption of milk and dairy products is lower in rural areas than in urban areas, even though milk is produced in rural areas.

2.1.2 Policies Influencing the Dairy Sector

Agriculture, including the dairy sector, is state controlled, and state governments are primarily responsible for development of the sector. The central government supplements the efforts of the state governments through various schemes for achieving accelerated growth of the sector. Despite the importance of dairying in the Indian economy, especially for the livelihoods of resource-poor farmers and landless laborers, government policy toward this sector has suffered from the lack of a clear and strong thrust and focus. The first attempt to conceive a set of policies for livestock development in India was the Royal Commission on Agriculture (1928). We can divide the government policies into three distinct phases; pre-Operation Flood, post-Operation Flood, and post-reform period.

There are also wide variations in per capita availability of milk in the country. The per capita availability of milk in major states and union territories is given in Annex Table 2.3. The average per capita availability is lowest in the eastern region and highest in the northern region (see Figure 2.3). The average per capita availability of milk during 2000-01 was highest in Punjab (997 gm/day), followed by Haryana (645 gm), Himachal Pradesh (354 gm), Rajasthan (300 gm), and Gujarat (296 gram). Only 10 states had higher than the national average per capita availability of milk (220 gram/day). The per capita availability is low in the eastern and northeastern states. Milk production and per capita availability in major states during TE 1998-00 are presented in Figure 2.4. The average per capita consumption of milk and dairy products is lower in rural areas than in urban areas, even though milk is produced in rural areas.

2.1.2 Policies Influencing the Dairy Sector

Agriculture, including the dairy sector, is state controlled, and state governments are primarily responsible for development of the sector. The central government supplements the efforts of the state governments through various schemes for achieving accelerated growth of the sector. Despite the importance of dairying in the Indian economy, especially for the livelihoods of resource-poor farmers and landless laborers, government policy toward this sector has suffered from the lack of a clear and strong thrust and focus. The first attempt to conceive a set of policies for livestock development in India was the Royal Commission on Agriculture (1928). We can divide the government policies into three distinct phases; pre-Operation Flood, post-Operation Flood, and post-reform period.

Figure 2.2 Share of milk production in India by state:

1980-82 and 1998-00

Source:

NDDB, 2003a.

Figure 2.3 Map showing the per capita availability of milk in India by state: 2000-01

Source: NDDB, 2003b.

Figure 2.4 Total milk production and per capita availability of milk in major states in India:

TE 2000-01

Source: GOI, 2003.

Figure 2.3 Map showing the per capita availability of milk in India by state: 2000-01

Source: NDDB, 2003b.

Figure 2.4 Total milk production and per capita availability of milk in major states in India:

TE 2000-01

Source: GOI, 2003.

One of the indicators of a sector's importance is the budget

allocation to that sector. The investment pattern in animal husbandry and

dairying during various plan periods is given in Annex Table 2.4. The plan

outlay (at current prices) of central and centrally sponsored schemes under

animal husbandry and dairying has increased from Rs. 22 crore in the First Plan

to Rs. 1,545.64 crore in the Ninth Plan and Rs. 2500 crore in the Tenth Plan.

The outlay for dairying increased from Rs. 781 crore in the First Plan to Rs.

900 crore in the Eighth Plan and then declined in the Ninth Plan to Rs. 469.5

crore (all figures are at current prices). The allocation to animal husbandry

and dairying as a percentage of total plan outlay varied from 0.98 percent

during the Fourth Plan to about 0.18 percent during the Ninth Plan (Figure

2.5). However, in most cases the bulk of the budget is eaten up by wages and

other administrative costs of the government departments. Although the dairy

sector occupies a pivotal position and its contribution to the agricultural

sector is the highest, the plan investment made so far does not appear

commensurate with its contribution and future potential for growth and

development.

The

low productivity of Indian cattle has been the central concern of livestock

policy throughout the last century. In the First Five Year Plan, the Key

Village Scheme (KVS) was launched to improve breeding, feed and fodder

availability, disease control, and milk production. To meet urban areas' need

for milk, the government promoted state-owned dairy plants to handle milk

procurement, processing, and marketing. In 1959, the government Delhi Milk

Scheme (DMS) was set up to supply milk to the urban population of Delhi. This

scheme adopted the method of departmental milk procurement from the

milk-producing areas around Delhi by setting up its own milk collection and

chilling centers. Though the collection was started from small milk vendors

initially, it ultimately ended up creating big contractors who purchased milk

from the small vendors and supplied it in bulk to the milk scheme. The same

policies and strategies continued in the Second Five-Year Plan. In 1976, the

National Commission on Agriculture concluded that the KVS could not meet its

objectives because, due to a shortage of funds, it did not stress feed and

fodder development and marketing of milk. The Third Plan emphasized the need to

develop dual-purpose animals for milk as well as draft use; crossbreeding of

nondescript indigenous cattle was introduced during this plan. The Intensive

Cattle Development Programme (ICDP) was launched in areas with high milk

potential.

Figure 2.5 Share of animal husbandry and dairying

outlay in total plan outlay during different plan periods

Source: GOI, 1999.

The disappointing performance of the dairy sector during the 1950s

and 1960s concerned policy makers, and the Government of India undertook a

far-reaching policy initiative. Dairy development through producers'

cooperatives and milk production based on milk sheds in the rural areas,

modeled on the successful experience of dairy cooperatives in Gujarat, became

the cornerstone of the new dairy sector policy. This policy initiative turned

the Indian dairy sector around and led to all-around growth with several

unarticulated spread effects.

The Government of India launched a massive dairy development

program popularly known as Operation Flood (OF) from 1971 to 1996. The program

was initially started with the help of the World Food Program (WFP) and later

continued with dairy commodity assistance from the European Economic Community

(EEC) and a soft loan/credit from the World Bank. Under this program, rural

producers were organized into cooperatives so they would have an assured

market, remunerative prices, and inputs and services for milk production

enhancement, such as better feed and fodder, breed improvement through

artificial insemination, and disease control measures. The program was unique

in its approach inasmuch as the gift dairy commodities received by India under

the program were not consumed by free distribution but were used to manufacture

liquid milk, and funds thus generated were reinvested in rural areas in milk

production enhancement activities. This coordinated and innovative effort has

greatly increased milk production and ushered in a "White

Revolution," making India the world's largest milk producer.

The program was implemented in three phases: OF-I (1970-1981),

OF-II (1981-85) and OF-III 1987-96). Operation Flood remained the pivot of

government policy in the field of dairy development in India, and the number of

city milk schemes and milk colonies begun in the 1950s and 1960s declined as

the regional and national milk grids started operating under OF. In metro

areas, government milk schemes coexisted with the Mother Dairies run under the

control of the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB); however, the former

kept selling milk at subsidized rates for long time for political reasons, and

Mother Dairies introduced aggressive, modern milk marketing and distribution

systems.

An indicator of the success of Operation Flood is the amount of

milk procured and supplied to consumers. Average milk procurement increased

from 2.56 million kg per day during Phase I to 11 million kg per day during

Phase III. However, there are variations in the proportion of milk procured to

total milk production across states. The striking pattern that emerges is the

predominance of cooperatives in Gujarat and Maharashtra. Between Phase I and

III, average liquid milk marketing increased from 27.8 lakh liters per day to

about 100 lakh liters per day.

In 1989, the Government of India launched a Technology Mission on

Dairy Development (TMDD) to coordinate the input programs for the dairy sector,

which ended in March 1999. An Integrated Dairy Development Programme (IDDP) in

non-Operation Flood, hilly, and backward areas was launched as a Centrally

Sponsored Plan Scheme during the Eighth Plan and continued during the Ninth and

Tenth Plans.

To promote domestic production, India adopted an

import-substitution strategy and protected the sector from external markets

through means such as quantitative restrictions on imports and exports and

canalization (restricting imports and exports through government or government

designated agencies). Competition within the organized sector was regulated

through licensing provisions, which prohibited new entrants into the milk-processing

sector. Milk powder and butter oil were available in the international market

at lower prices, which made reconstitution of milk from these products cheaper

than collecting and selling fresh milk. It was therefore necessary to restrict

the availability of these cheap imports to encourage the indigenous production.

The third phase of Indian dairy policy started in the early 1990s,

when the Government of India introduced major trade policy reforms that favored

increasing privatization and liberalization of the economy. The dairy industry

was delicensed in 1991 with a view to encouraging private sector participation

and investment in the sector. However, in response to sociopolitical pressures,

the government introduced the Milk and Milk Products Order (MMPO) in 1992 under

the Essential Commodities Act of 1955 to regulate milk and dairy product

production. The order required permission from state/central registration

authorities to set up units handling more than 10,000 liters of milk per day or

milk solids up to 500 tons per annum (TPA), depending on the capacity of the

plant. The order included sanitary and hygienic regulations to ensure product

quality. The status of registrations granted under the MMPO as of March 31,

2002, is given in Annex Table 2.5.

However, concerns were raised about these government controls and

licensing requirements for restricting large Indian and multinational players

from making significant investments in this sector. The government has amended

the MMPO from time to time; the major amendment was made in March 2002, when

restrictions on setting up milk processing and milk product manufacturing

plants were removed and the concept of milkshed was also abolished. This

amendment is expected to facilitate the entry of large companies, which would

definitely increase competition in the domestic markets.

The

second major development in Indian dairy sector policy came when India signed

the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture (URAA) in 1994 and became a member

of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which made India open up its dairy

sector to world markets. The import and export of dairy products was delicensed

and decanalized, and trade in dairy products was allowed freely, with certain

inspection requirements. The first major step was taken in 1994-95, when the

import of skim milk powder (SMP) and butter oil was decanalized; restrictions

on the remaining products were removed in April 2002. Moreover, there was a

significant reduction in the import tariffs on dairy products after trade

liberalization. However, India had bound its import tariffs for dairy products

at low levels in the Uruguay Round schedules.

2.1.3 Livestock Population Trends

India has one of the largest livestock populations in

the world, accounting for about 57 percent of the world buffalo population and

16 percent of the cattle population (GOI, 2002). The growth pattern of the

livestock population during 1951 and 1997 is given in Table 2.4. Between 1951

and 2002, the cattle population increased from 155.3 million to 175.1 million.

The cattle population grew by less than 1 percent per year between 1951 and

1997, while the buffalo population almost doubled (2.24% per year) during the

same period. The cattle and buffalo stocks witnessed a significant acceleration

in growth during 1977 to 1982 compared to the previous five years. The rate of

increase in the cattle (2.04%/year) and buffalo (2.66%/year) populations was

highest between 1956 and 1961 among all the periods considered. The turning

point in the composition of the draft animal population was 1977; male cattle

population declined from 73.22 million to 61.14 million between 1977 and 1982,

and the corresponding decline among male buffalo population was over 1.96

million (GOI, 1999). This declining trend, however, is not uniform across the

states. Agriculturally advanced states such as Punjab, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh,

Kerala, and Tamil Nadu witnessed a sharp decline in the male draft animal

population due to farm mechanization, while the less progressive and hilly states

such as Assam, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and West Bengal showed increasing

dependence on work animals.

Table 2.4 Growth pattern of livestock population in

India: 1951-1992 (millions)

| Species |

1951 |

1956 |

1961 |

1966 |

1972 |

1977 |

1982 |

1987 |

1992 |

1997* |

| Cattle |

155.3 |

158.7 |

175.6 |

176.2 |

178.3 |

180.0 |

192.5 |

199.7 |

204.6 |

175.0 |

| Adult

female cattle |

54.4 |

47.3 |

51.0 |

51.8 |

53.4 |

54.6 |

59.21 |

62.07 |

64.36 |

- |

| Buffalo |

43.4 |

44.9 |

51.2 |

53.0 |

57.4 |

62.0 |

69.78 |

75.97 |

84.21 |

84.03 |

| Adult

female buffalo |

21.0 |

21.7 |

24.3 |

25.4 |

28.6 |

31.3 |

32.5 |

39.13 |

43.81 |

- |

| Total

bovines |

198.7 |

203.6 |

226.8 |

229.2 |

235.7 |

242.0 |

262.4 |

257.8 |

289.0 |

259.0 |

| Total

livestock |

292.8 |

306.6 |

335.4 |

344.1 |

353.4 |

369.0 |

419.6 |

445.3 |

470.9 |

452.5 |

| Annual

growth rates (%) |

1951-56 |

1956-61 |

1961-66 |

1966-72 |

1972-77 |

1977-82 |

1982-87 |

1987-92 |

1992-97 |

|

| Cattle |

0.43 |

2.04 |

0.07 |

0.24 |

0.19 |

1.35 |

0.74 |

0.48 |

- |

|

| Adult

female cattle |

-2.76 |

1.52 |

0.31 |

0.61 |

0.45 |

1.63 |

0.95 |

0.73 |

- |

|

| Buffalo |

0.68 |

2.66 |

0.69 |

1.61 |

1.55 |

2.39 |

1.71 |

2.08 |

- |

|

| Adult

female buffalo |

0.66 |

2.29 |

0.89 |

2.40 |

1.82 |

0.76 |

3.78 |

2.28 |

- |

|

| Total

bovines |

0.49 |

2.18 |

0.21 |

0.56 |

0.53 |

1.63 |

1.01 |

0.94 |

- |

|

| Total

livestock |

0.93 |

1.81 |

0.51 |

0.53 |

0.87 |

2.60 |

1.20 |

1.12 |

- |

|

Note: *:

Excludes the data for Bihar, Dadra Nagar, and Haveli.

Source:

GOI, Basic Animal Husbandry Statistics 2002, Department of Animal Husbandry and

Dairying, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India.

The crossbreeding program, after a slow start during the 1960s,

spread very fast, and the successive rounds of livestock census clearly

established the speed with which crossbreeding spread in different parts of the

country. In 1992, crossbred cattle constituted about 4.5 percent of total

cattle and about 9.5 percent of total cows in the country. In states such as

Punjab and Kerala, the proportion of crossbred cows is substantially higher

than in other states. The proportion of crossbred cows increased while that of

indigenous cows declined, indicating the increasing importance of crossbred

cows over indigenous cows. The proportion of female buffaloes also increased

significantly, from 30.2 percent to 36 percent between 1982 and 1992.

In the global context, the performance of the Indian dairy sector

appears impressive in terms of livestock population and total milk production

but extremely poor in terms of productivity. The main reasons for low yields

are inadequate availability of feeds and fodder in all seasons,

non-availability of timely and good animal health care and breeding services,

and lack of credit. The average milk productivity per year per cow increased

from 731 kg in 1989-91 to about 1,014 kg in 1999. Although average

annual milk production per animal has improved substantially, it is far below

the world average (2,071 kg/year) and that of countries such as Israel (8,785

kg), the United States (8,043 kg), and Denmark (6,565 kg). The available data on

milk yield indicate that average productivity went up substantially in the case

of cows during the 1970s and 1980s. There is an increase in the yield of

buffaloes also, but it is less sharp than that of cows. A key factor accounting

for the sharper increase in cow milk yield is the increasing proportion of

crossbred cows.

As

in milk production and availability, there are wide interstate variations in

milk yields (Table 2.5). In general, buffaloes have higher yields than

indigenous cows, but crossbred cows are more productive than either indigenous

cows or buffaloes. The average productivity of local cows is highest in Haryana

(4.11 kg/day), followed by Punjab (2.88 kg/day) and Gujarat (2.84 kg/day). For

crossbred cows it is highest in Punjab (8.36 kg/day), followed by Gujarat (7.96

kg/day) and West Bengal (7.82 kg/day). The average productivity of buffaloes is

highest in West Bengal (6.26 kg/day), followed by Haryana (5.64 kg/day) and

Punjab (5.62 kg/day).

Table 2.5 Statewide yield rate of milk (kg) per animal per day of

cow and buffalo in milk (1996-97)

| States |

Cows |

Buffalo |

|

| Indigenous |

Crossbred |

||

| Andhra

Pradesh |

1.34 |

5.07 |

2.89 |

| Bihar |

1.63 |

4.81 |

3.50 |

| Gujarat |

2.84 |

7.96 |

3.80 |

| Haryana |

4.11 |

6.52 |

5.64 |

| Himachal

Pradesh |

1.69 |

3.32 |

3.02 |

| Karnataka |

1.82 |

5.57 |

2.40 |

| Kerala |

2.22 |

5.63 |

4.83 |

| Madhya

Pradesh |

1.18 |

5.56 |

2.98 |

| Maharashtra |

1.50 |

6.79 |

3.56 |

| Orissa |

0.48 |

3.93 |

1.84 |

| Punjab |

2.88 |

8.36 |

5.62 |

| Rajasthan |

2.79 |

5.31 |

4.01 |

| Tamil Nadu |

2.39 |

5.55 |

3.58 |

| Uttar

Pradesh |

2.04 |

5.80 |

3.74 |

| West

Bengal |

2.15 |

7.82 |

6.26 |

| All India |

1.84 |

6.16 |

3.94 |

Source:

GOI, Basic Animal Husbandry Statistics 1999, Department of Animal Husbandry and

Dairying, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India.

2.2.1 Characteristics of the Indian Dairy Sector

Some of the structural shifts that have taken place in the Indian dairy sector include (i) an increasing shift to milk production as a major objective of rearing bovines, (ii) replacement of animal power with mechanical power in developed regions of the country, and (iii) increasing proportions of crossbred cattle in the total cattle population.

In states like Kerala and Punjab, crossbred cattle have virtually replaced indigenous cattle; they account for over three-quarters of the total milk cattle population in Punjab and 70 percent in Kerala (GOI, 2003). The other states with high crossbred cattle populations are Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and West Bengal, though breedable female crossbreds account for less than 10 percent of total breedable females in Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal (Annex Table 2.6).

No reliable macro-level data about size distribution of livestock are available, so it is extremely difficult to describe the structural changes in milk production activity. The number and species of milk animals kept by farmers varies considerably across regions/states, but the average number of dairy animals hardly exceeds three to four in most parts of the country. However, in certain parts of Punjab, Haryana, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh, dairy animal holdings are larger. Certain micro-level studies indicate that there has not been much change in the average size of milk animal population in most parts of the country, except in a few pockets in the northern and western region. A study by Shukla and Brahmankar (1999) showed that the scale of milk production had not changed significantly in Operation Flood areas between 1988-89 and 1995-86. The average milk animal holding size has remained more or less same in all zones (south, east, and west) during this period except for the north, where the proportion of households having four or more milk animal increased from 24 percent in 1988-89 to about 30 percent in 1995-96. On the other hand, in the eastern region, the proportion of households having at least one animal increased from 44.9 percent in 1988-89 to 60 percent in 1995-96. At the national level, the distribution remained almost the same between 1986-87 and 1991-92 (Table 2.6).

Table 2.6 Changes in average number of bovine population in India: 1986-87 and 1991-92

2.2.1 Characteristics of the Indian Dairy Sector

Some of the structural shifts that have taken place in the Indian dairy sector include (i) an increasing shift to milk production as a major objective of rearing bovines, (ii) replacement of animal power with mechanical power in developed regions of the country, and (iii) increasing proportions of crossbred cattle in the total cattle population.

In states like Kerala and Punjab, crossbred cattle have virtually replaced indigenous cattle; they account for over three-quarters of the total milk cattle population in Punjab and 70 percent in Kerala (GOI, 2003). The other states with high crossbred cattle populations are Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and West Bengal, though breedable female crossbreds account for less than 10 percent of total breedable females in Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal (Annex Table 2.6).

No reliable macro-level data about size distribution of livestock are available, so it is extremely difficult to describe the structural changes in milk production activity. The number and species of milk animals kept by farmers varies considerably across regions/states, but the average number of dairy animals hardly exceeds three to four in most parts of the country. However, in certain parts of Punjab, Haryana, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh, dairy animal holdings are larger. Certain micro-level studies indicate that there has not been much change in the average size of milk animal population in most parts of the country, except in a few pockets in the northern and western region. A study by Shukla and Brahmankar (1999) showed that the scale of milk production had not changed significantly in Operation Flood areas between 1988-89 and 1995-86. The average milk animal holding size has remained more or less same in all zones (south, east, and west) during this period except for the north, where the proportion of households having four or more milk animal increased from 24 percent in 1988-89 to about 30 percent in 1995-96. On the other hand, in the eastern region, the proportion of households having at least one animal increased from 44.9 percent in 1988-89 to 60 percent in 1995-96. At the national level, the distribution remained almost the same between 1986-87 and 1991-92 (Table 2.6).

Table 2.6 Changes in average number of bovine population in India: 1986-87 and 1991-92

Cattle

|

Buffalo

|

|||||||

Male

|

Female

|

Male

|

Female

|

|||||

| 1986-87 |

1991-92 |

1986-87 |

1991-92 |

1986-87 |

1991-92 |

1986-87 |

1991-92 |

|

| Marginal |

0.72 |

0.68 |

0.59 |

0.65 |

0.18 |

0.15 |

0.36 |

0.43 |

| Small |

1.49 |

1.58 |

1.07 |

1.29 |

0.30 |

0.30 |

0.71 |

0.90 |

| Semi-medium |

1.92 |

1.83 |

1.49 |

1.56 |

0.44 |

0.38 |

1.05 |

1.18 |

| Medium |

2.64 |

2.20 |

2.14 |

1.91 |

0.60 |

0.48 |

1.76 |

1.54 |

| Large |

3.58 |

2.45 |

3.42 |

2.45 |

0.76 |

0.57 |

2.41 |

1.93 |

| All |

1.20 |

1.16 |

0.95 |

1.03 |

0.28 |

0.25 |

0.65 |

0.74 |

| Category |

Cattle |

Buffaloes |

Sheep |

Goats |

||

| Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|||

| 1986-87 |

||||||

| Marginal |

45.8 |

37.4 |

11.7 |

23.0 |

15.2 |

38.5 |

| Small |

29.9 |

21.5 |

6.1 |

14.2 |

9.5 |

19.4 |

| Semi-medium |

26.8 |

20.7 |

6.1 |

14.6 |

8.7 |

15.3 |

| Medium |

20.0 |

16.2 |

4.6 |

13.3 |

7.6 |

10.0 |

| Large |

5.9 |

5.7 |

1.3 |

4.0 |

4.6 |

4.3 |

| All Size

Classes |

128.4 |

101.5 |

29.7 |

69.2 |

45.5 |

87.4 |

| 1991-92 |

||||||

| Marginal |

38.2 |

36.6 |

8.7 |

24.4 |

13.8 |

36.2 |

| Small |

28.3 |

23.1 |

5.3 |

16.2 |

8.7 |

18.8 |

| Semi-medium |

24.2 |

20.7 |

5.1 |

15.6 |

7.1 |

14.2 |

| Medium |

17.4 |

15.1 |

3.8 |

12.2 |

5.6 |

9.3 |

| Large |

4.7 |

4.7 |

1.1 |

3.7 |

2.5 |

3.8 |

| All

Classes |

112.8 |

100.3 |

24.0 |

72.0 |

37.7 |

82.3 |

Dairying has historically been an unorganized activity in India.

The traditional or unorganized sector consisting of milk vendors/dudhias and sweet shops, as well as numerous

other types of market factors, is still a dominant (84%) sector in the liquid

milk market. Like nearly all developing countries, India exhibits coexisting

"organized" and "unorganized" sectors for the marketing of

milk and dairy products. Sometimes called the "informal" sector, the

unorganized sector may be more usefully thought of as the traditional milk

market sector, comprising the marketing of raw milk and traditional products such

as locally manufactured ghee, fresh cheese, and sweets. The organized or formal

sector is relatively new in historical terms, and consists of western-style

dairy processing based on pasteurization, although adapted to the Indian market

in terms of products. In some cases, the traditional sector is quite well

organized, with a complex net of market agents. It may also be relatively

formal, in that market agents may pay municipal fees and have vendor licenses,

albeit not specifically for the dairy trade.

The reasons underlying the existence of a large informal or traditional sector are the same as in other countries where it is important: consumers are unwilling to pay the additional costs of pasteurization and packaging, which can raise retail prices by over 100 percent, and consumers often regard raw milk and traditional products obtained from reliable vendors as of better quality than formally processed dairy products. It should be noted that, unlike some countries, in India the government has generally adopted a laissez-faire approach to the informal sector, which has allowed it to expand with the growth in demand and serve both small farmers and resource-poor consumers. Of the estimated milk production of about 78 million tons during 1999-2000, the organized sector, primarily through dairy cooperatives and organized private dairies, handled 10 to 12 percent of the total milk production or 15 percent of the marketed surplus, and large, complex, highly differentiated traditional private trade in milk and dairy products handled the rest.

Smallholder farmers are caught in a situation of low returns, inaccessibility of resources and markets, non-availability of adequate production inputs and services, and many other social and economic constraints. The service sector, which is mostly managed and controlled by the government, is often inadequate and sometimes insensitive to farmers' needs. In the first two decades of Indian independence, milk production was stagnant, and the only successful experience was of the Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers' Union, better known as Amul or the "Anand Pattern." Amul's experience inspired the then prime minister of India Shri. Lal Bahadur Shastri to establish the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB), which was set up in 1965 to promote the dairy industry in rural India by replicating the Anand Pattern. The Anand Pattern is a three-tiered structure in which farmers organize themselves into dairy cooperative societies at the village level; these village level cooperatives are organized into a district-level union; the district-level unions federate into a state-level cooperative organization (Figure 2.6). At the national level, the National Cooperative Dairy Federation of India (NCDFI) coordinates the efforts of all state-level cooperative dairy federations.

The organized sector, consisting of 678 dairy plants registered under the MMPO, mainly in cooperative and private sector has grown rapidly during the last decade. The statewide number of milk-processing plants registered under the MMPO is given in Annex Table 2.5. By December 2002, about 101,000 dairy cooperative societies were organized, involving about 11.2 million farmer members. The average milk procurement during April-December 2002 was 17.24 million kg per day (3 percent higher than the previous year), and average milk marketed was about 13.7 million liters (GOI, 2003). The milk-processing capacity in the country has increased substantially: from 10,000-20,000 liters per day in the 1950s to 100,000 liters per day in the 1970s, 500,000 liters per day in the 1980s, and over 1 million liters per day in the 1990s. As discussed in the earlier part of this chapter, until the early 1990s, milk processing was mainly reserved for the cooperative sector through licensing.

However, as a part of domestic economic reforms and commitments to the WTO, the Indian dairy sector was liberalized in a phased manner starting with partial opening-up in 1991; in March 2002, the government removed all restrictions on setting up new milk-processing capacity.

Following partial decontrol of the dairy sector in the early 1990s, many private sector players entered the market and set up milk-processing facilities, mostly in milk surplus areas. Some of the private sector plants also adopted the Amul model by creating informal contacts with local farmers and providing various inputs and services to the farmers. For example, Nestle has made large investments in its milkshed to improve productivity levels and the quality of raw milk. However, a large proportion of private dairy plants depend on contractors/subcontractors to meet their raw material requirement. Some of the arrangements between processors and producers are shown in Figure 2.7.

The reasons underlying the existence of a large informal or traditional sector are the same as in other countries where it is important: consumers are unwilling to pay the additional costs of pasteurization and packaging, which can raise retail prices by over 100 percent, and consumers often regard raw milk and traditional products obtained from reliable vendors as of better quality than formally processed dairy products. It should be noted that, unlike some countries, in India the government has generally adopted a laissez-faire approach to the informal sector, which has allowed it to expand with the growth in demand and serve both small farmers and resource-poor consumers. Of the estimated milk production of about 78 million tons during 1999-2000, the organized sector, primarily through dairy cooperatives and organized private dairies, handled 10 to 12 percent of the total milk production or 15 percent of the marketed surplus, and large, complex, highly differentiated traditional private trade in milk and dairy products handled the rest.

Smallholder farmers are caught in a situation of low returns, inaccessibility of resources and markets, non-availability of adequate production inputs and services, and many other social and economic constraints. The service sector, which is mostly managed and controlled by the government, is often inadequate and sometimes insensitive to farmers' needs. In the first two decades of Indian independence, milk production was stagnant, and the only successful experience was of the Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers' Union, better known as Amul or the "Anand Pattern." Amul's experience inspired the then prime minister of India Shri. Lal Bahadur Shastri to establish the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB), which was set up in 1965 to promote the dairy industry in rural India by replicating the Anand Pattern. The Anand Pattern is a three-tiered structure in which farmers organize themselves into dairy cooperative societies at the village level; these village level cooperatives are organized into a district-level union; the district-level unions federate into a state-level cooperative organization (Figure 2.6). At the national level, the National Cooperative Dairy Federation of India (NCDFI) coordinates the efforts of all state-level cooperative dairy federations.

The organized sector, consisting of 678 dairy plants registered under the MMPO, mainly in cooperative and private sector has grown rapidly during the last decade. The statewide number of milk-processing plants registered under the MMPO is given in Annex Table 2.5. By December 2002, about 101,000 dairy cooperative societies were organized, involving about 11.2 million farmer members. The average milk procurement during April-December 2002 was 17.24 million kg per day (3 percent higher than the previous year), and average milk marketed was about 13.7 million liters (GOI, 2003). The milk-processing capacity in the country has increased substantially: from 10,000-20,000 liters per day in the 1950s to 100,000 liters per day in the 1970s, 500,000 liters per day in the 1980s, and over 1 million liters per day in the 1990s. As discussed in the earlier part of this chapter, until the early 1990s, milk processing was mainly reserved for the cooperative sector through licensing.

However, as a part of domestic economic reforms and commitments to the WTO, the Indian dairy sector was liberalized in a phased manner starting with partial opening-up in 1991; in March 2002, the government removed all restrictions on setting up new milk-processing capacity.

Following partial decontrol of the dairy sector in the early 1990s, many private sector players entered the market and set up milk-processing facilities, mostly in milk surplus areas. Some of the private sector plants also adopted the Amul model by creating informal contacts with local farmers and providing various inputs and services to the farmers. For example, Nestle has made large investments in its milkshed to improve productivity levels and the quality of raw milk. However, a large proportion of private dairy plants depend on contractors/subcontractors to meet their raw material requirement. Some of the arrangements between processors and producers are shown in Figure 2.7.

As the trade liberalization in agriculture and dairy

products has progressed, attention has increasingly focused on technical

measures such as food safety, regulations, labeling requirements, and quality

and compositional standards. The WTO Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary

Measures (SPS) sets important requirements for adoption and implementation of

food safety and quality and recognizes the standards, guidelines, and

recommendations determined by the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC). CAC

standards have been formulated for a majority of dairy products, such as

maximum permissible levels of contaminants/additives and hygienic requirements

for production. However, there has been increased concern about these measures,

particularly in the case of smallholder dairy production systems, as their

application necessarily adds to the transactions cost of international trade.

Source: Personal discussions with private sector.

The chemical contaminants for which CAC standards have been set

include heavy metals (lead), 85 pesticide residues, and 10 veterinary drug

residues in milk and dairy products. However, the Indian national standards are

lower than international/developed country standards, and infrastructure is

deficient due to lack of resources and inadequate information. In the case of

lead, for example, maximum levels of 0.05 ppm in butter and 0.02 ppm in milk

have been recommended by the Codex Committee on Food Additives and

Contaminants, whereas the Indian standard is 2.5 ppm for milk. The CAC has also

set maximum residue limit (MRL) for 85 pesticide residues, compared with

India's 24 pesticides. Likewise, the CAC has set MRLs for 10 veterinary drug

residues, whereas India has not yet set MRLs for veterinary drugs. The 33rd Codex Committee on Food Additives and

Contaminants has recommended an MRL of 0.5 ppb for Aflatoxin M1 in milk, compared to an Indian

national limit of 0.03 ppm. The CAC has incorporated several provisions in its

proposed Model Certificate for Export and Import of Milk Products that would be

extremely difficult for most developing countries, including India, to comply

with.

The CAC is also concerned about the microbiological quality of

milk and dairy products, and has recommended measures to minimize

microbiological contamination. CAC guidelines stipulate that the raw material

should be produced in a way that minimizes bacterial count, growth, and

contamination. To achieve this, the CAC recommends the application of the

Principles of Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) system.

Smallholder production in India is often based on hand milking,

with few or no cooling facilities and inappropriate animal housing and poor

animal health protection in most parts of the country. The Indian dairy

industry will have to gear up to meet international regulatory requirements and

ensure that dairy plants get HACCP certification. Some steps have already been

taken in this direction, but there is a long way to go. The National Dairy

Development Board, under its Perspective Plan 2010, has started a Clean Milk

Production Programme, and more than 12,000 village dairy cooperative societies

in 16 states have been brought under it. Similar initiatives have been taken by

various state milk marketing federations and other agencies. Sixty-three

milk-processing plants/dairies in the cooperative sector have obtained

International Standards Organization (ISO)/HACCP certification with assistance

from NDDB. Private sector dairy plants have taken similar steps to ensure the

quality of raw material; for example, Nestle has provided bulk coolers to

farmer societies and launched awareness programs in the area. However, current

levels of infrastructure and financial resources are too low to achieve the

desired standards.

Animal welfare, which includes establishing norms for animal

protection on the farm, during transport, and at the time of slaughter, is a

growing source of concern among animal protection organizations, consumers, and

decision makers. Although animal welfare is not currently covered under the WTO

Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement, these issues are coming under increasing

public scrutiny. Two main types of policies relate to animal welfare: (i) to

support production methods that promote animal welfare and (ii) to impose

requirements on imports so that acceptable standards of animal welfare are

applied during production and transportation. National authorities must seek to

reduce the negative effects of commercialization of livestock farming and trade

on animal welfare. The WTO recognizes the Office International des Epizooties (OIE) as the

international organization responsible for the development and promotion of

international animal health standards, guidelines, and recommendations

affecting trade in live animals and livestock products. These OIE activities

cover safety procedures for raw materials during production and first-stage

processing before they enter the market.

Since the introduction of an extensive crossbreeding program, the

susceptibility of these exotic breeds to various diseases has increased. In

order to reduce morbidity and mortality, state governments are attempting to

provide better health care facilities through polyclinics and veterinary

hospitals/dispensaries/first-aid centers, including mobile veterinary

dispensaries. At present, 26,717 polyclinics/hospitals/dispensaries and 28,195

veterinary aid centers supported by about 250 disease diagnostic laboratories

are functioning in the states and union territories. In addition, there are

about 26 veterinary vaccine production units, 19 in the public sector and 7 in

the private sector. The import of vaccines by private agencies is also

permitted. The statewide details of veterinary institutions in the country are

given in Annex Table 2.7.

The Government of India and the state governments have initiated various schemes to provide livestock health services and disease control. In most of the states, a large proportion of the budget is spent on salary and wages and little is left for providing services. The Government of India has proposed a comprehensive scheme, "Livestock Health and Disease Control" in three components: (i) control of animal diseases, (ii) Foot and Mouth Disease Control Programme (new), and (iii) National Project on Rinderpest Eradication, by merging various schemes during the Tenth Five Year Plan.

The central government provides assistance to state/union territory governments for control of tuberculosis, brucellosis, and swine fever; sterility and abortions in bovines; control of emerging and exotic diseases; strengthening of state veterinary biological production centers and disease diagnostic laboratories; and creation of disease-free zones. The incidence of livestock diseases in India during 2001 is given in Annex Table 2.8.

Since in March 1998, the country has been provisionally free from rinderpest disease; however, the government has initiated a National Project on Rinderpest Eradication to achieve the final stage of freedom from that disease and from contagious bovine pleuro pneumonia by strengthening veterinary services as per the guidelines prescribed by the OIE. Surveys have been initiated in about 1,162 villages to generate information. Eradication of rinderpest is a three-stage process: (i) provisional freedom from the disease, (ii) substantive freedom from the disease, (iii) freedom from rinderpest infection. The successful implementation of this program would benefit livestock farmers, boost export of livestock products, and pave the way for control programs against other diseases, such as foot-and-mouth disease (FMD).

FMD is a major disease facing Indian livestock; it reduces milk yields and draft power. The disease is prevalent all over the country. Strains O, A, and Asia1 are active, while strain C has not been reported since 1996. No systematic control and vaccination program against FMD exists in the country, even though there is a massive but sporadic vaccination program. More than 25 million vaccinations are carried out every year against FMD, but this program is ineffective, as FMD protection is based on herd immunity. Over 85 percent of the individuals in an area have to be vaccinated to establish herd immunity. The population at risk in the country (all susceptible species) is about 420 million, and barely 5 percent of the animals at risk are vaccinated. The central government has proposed a new Foot and Mouth Disease Control Programme in specified areas in the country under a macro-management approach during the Tenth Plan.

The Government of India and the state governments have initiated various schemes to provide livestock health services and disease control. In most of the states, a large proportion of the budget is spent on salary and wages and little is left for providing services. The Government of India has proposed a comprehensive scheme, "Livestock Health and Disease Control" in three components: (i) control of animal diseases, (ii) Foot and Mouth Disease Control Programme (new), and (iii) National Project on Rinderpest Eradication, by merging various schemes during the Tenth Five Year Plan.

The central government provides assistance to state/union territory governments for control of tuberculosis, brucellosis, and swine fever; sterility and abortions in bovines; control of emerging and exotic diseases; strengthening of state veterinary biological production centers and disease diagnostic laboratories; and creation of disease-free zones. The incidence of livestock diseases in India during 2001 is given in Annex Table 2.8.

Since in March 1998, the country has been provisionally free from rinderpest disease; however, the government has initiated a National Project on Rinderpest Eradication to achieve the final stage of freedom from that disease and from contagious bovine pleuro pneumonia by strengthening veterinary services as per the guidelines prescribed by the OIE. Surveys have been initiated in about 1,162 villages to generate information. Eradication of rinderpest is a three-stage process: (i) provisional freedom from the disease, (ii) substantive freedom from the disease, (iii) freedom from rinderpest infection. The successful implementation of this program would benefit livestock farmers, boost export of livestock products, and pave the way for control programs against other diseases, such as foot-and-mouth disease (FMD).

FMD is a major disease facing Indian livestock; it reduces milk yields and draft power. The disease is prevalent all over the country. Strains O, A, and Asia1 are active, while strain C has not been reported since 1996. No systematic control and vaccination program against FMD exists in the country, even though there is a massive but sporadic vaccination program. More than 25 million vaccinations are carried out every year against FMD, but this program is ineffective, as FMD protection is based on herd immunity. Over 85 percent of the individuals in an area have to be vaccinated to establish herd immunity. The population at risk in the country (all susceptible species) is about 420 million, and barely 5 percent of the animals at risk are vaccinated. The central government has proposed a new Foot and Mouth Disease Control Programme in specified areas in the country under a macro-management approach during the Tenth Plan.

Livestock and livestock waste produce ammonia, carbon dioxide,

methane, ozone, nitrous oxide, and other trace gases, which affect the world's

atmosphere and contribute to global warming. Of all the gases, methane is the

most important in causing global climate change. It is largely a product of

animal production and manure management, which contribute about 16 percent of

total methane volume.

In India, livestock is an integral part of crop farming, and resource use in mixed farming (crop + livestock) is often highly self-reliant, as nutrients and energy flow from crops to livestock and back. Such a system offers positive incentives to compensate for environmental effects ("internalize the environmental costs"), making them less damaging or more beneficial to the natural resource base. Pollution problems in rural areas are internalized, as the small amount of waste produced is used as fuel or organic manure. However, small-scale urban or peri-urban production systems (which are dependent on external supplies of feed, energy, and other inputs and are strongly market driven), if not properly controlled, may create environmental pollution. Therefore, the challenge is to identify regulations and incentives that force the polluter to internalize the environmental costs at a minimum cost to the consumer. In India, there are no environmental regulations related to milk production in rural areas; there are regulations for peri-urban and urban dairy farming, but the implementation is extremely poor.

In India, livestock is an integral part of crop farming, and resource use in mixed farming (crop + livestock) is often highly self-reliant, as nutrients and energy flow from crops to livestock and back. Such a system offers positive incentives to compensate for environmental effects ("internalize the environmental costs"), making them less damaging or more beneficial to the natural resource base. Pollution problems in rural areas are internalized, as the small amount of waste produced is used as fuel or organic manure. However, small-scale urban or peri-urban production systems (which are dependent on external supplies of feed, energy, and other inputs and are strongly market driven), if not properly controlled, may create environmental pollution. Therefore, the challenge is to identify regulations and incentives that force the polluter to internalize the environmental costs at a minimum cost to the consumer. In India, there are no environmental regulations related to milk production in rural areas; there are regulations for peri-urban and urban dairy farming, but the implementation is extremely poor.

Annex Table 2.1 Per capita monthly consumption expenditure for a

period of 30 days on milk and milk products in rural and urban areas: 1970-71 to

1999-2000 (Rupees)

| NSS

Round |

Milk and Milk Products

|

Meat, Egg, Fish

|

Total Food

|

Total Nonfood

|

Total Expenses

|

Avg. size of Household

|

| 25th Round (1970-71) |

||||||

| Rural |

3.03 (11.7)

|

1.02

|

25.98

|

9.33

|

35.91

|

-

|

| Urban |

5.01 (14.7)

|

1.90

|

34.04

|

18.81

|

52.85

|

-

|

| 27th Round (1972-73) |

||||||

| Rural |

3.22

|

1.09

|

32.16

|

12.01

|

44.17

|

5.22

|

| Urban |

5.91

|

2.07

|

40.84

|

22.49

|

63.33

|

4.72

|

| 32nd Round (1977-78) |

||||||

| Rural |

5.29

|

1.84

|

44.33

|

24.56

|

68.89

|

5.22

|

| Urban |

9.16

|

3.33

|

57.67

|

38.48

|

96.15

|

4.89

|

| 38th Round (1982) |

||||||

| Rural |

8.45

|

3.40

|

73.73

|

38.71

|

112.45

|

5.20

|

| Urban |

15.15

|

5.92

|

96.97

|

67.06

|

164.03

|

4.85

|

| 42nd Round (1986-87) |

||||||

| Rural |

13.48

|

5.25

|

92.55

|

48.38

|

140.93

|

5.26

|

| Urban |

23.32

|

9.25

|

128.99

|

93.66

|

222.65

|

4.79

|

| 43rd Round (1987-88) |

||||||

| Rural |

13.63

|

5.11

|

100.82

|

57.28

|

158.10

|

5.08

|

| Urban |

23.83

|

8.85

|

139.75

|

110.18

|

249.93

|

4.71

|

| 44th Round (1988-89) |

||||||

| Rural |

15.65

|

6.12

|

111.80

|

63.30

|

175.10

|

5.17

|

| Urban |

26.74

|

10.59

|

152.49

|

114.36

|

266.85

|

4.87

|

| 45th Round (1989-90) |

||||||

| Rural |

18.35

|

6.84

|

121.78

|

67.68

|

189.46

|

4.96

|

| Urban |

29.53

|

11.42

|

165.46

|

132.54

|

298.00

|

4.66

|

| 46th Round (1990-91) |

||||||

| Rural |

19.04

|

7.08

|

133.34

|

68.70

|

202.12

|

4.81

|

| Urban |

32.37

|

12.27

|

185.77

|

140.00

|

326.75

|

4.55

|

| 47th Round (July-Dec.

1991) |

||||||

| Rural |

21.90

|

8.20

|

153.50

|

89.91

|

243.50

|

5.00

|

| Urban |

37.21

|

13.49

|

207.77

|

162.57

|

370.34

|

4.73

|

| 48th Round (Jan. -Dec. 1992) |

||||||

| Rural |

23.00

|

8.00

|

161.00

|

87.00

|

247.00

|

5.20

|

| Urban |

42.00

|

14.00

|

224.00

|

175.00

|

399.00

|

4.80

|

| 49th Round (Jan. -June

1993) |

||||||

| Rural |

23.00

|

9.00

|

159.00

|

85.00

|

244.00

|

5.10

|

| Urban |

41.00

|

14.00

|

221.00

|

162.00

|

382.00

|

4.60

|

| 50th Round (July 1993-June

1994) |

||||||

| Rural |

27.00

|

9.40

|

178.00

|

104.00

|

281.00

|

4.90

|

| Urban |

45.00

|

15.50

|

250.00

|

208.00

|

458.00

|

4.50

|

| 51st Round (July

1994-June 1995) |

||||||

| Rural |

27.00

|

10.00

|

189.00

|

121.00

|

309.00

|

4.90

|

| Urban |

49.00

|

17.00

|

271.00

|

237.00

|

508.00

|

4.60

|

| 52nd Round (July

1995-June 1996) |

||||||

| Rural |

32.38

|

10.94

|

207.75

|

136.53

|

344.29

|

5.00

|

| Urban |

56.45

|

19.11

|

299.98

|

299.28

|

599.26

|

4.60

|

| 53rd Round (Jan. -Dec.

1997) |

||||||

| Rural |

39.31

|

11.79

|

231.99

|

163.02

|

395.01

|

5.00

|

| Urban |

62.75

|

19.58

|

320.26

|

325.19

|

645.44

|

4.60

|

| 54th Round (Jan. -June 1998) |

||||||

| Rural |

36.54

|

12.65

|

232.40

|

149.67

|

382.07

|

5.00

|

| Urban |

64.63

|

21.94

|

339.71

|

344.57

|

684.27

|

4.70

|

| 55th Round (July 99-June

2000) |

||||||

| Rural |

42.56 (21.6)

|

16.14

|

288.80

|

197.28

|

486.07

|

5.00

|

| Urban |

74.18 (16.7)

|

26.77

|

410.86

|

444.10

|

854.96

|

5.00

|

Source:

NSSO, 2001.

Annex Table 2.2 Milk production trends in different states and union territories of India: 1991-92 to 2000-01 (thousands of metric tons)

Annex Table 2.2 Milk production trends in different states and union territories of India: 1991-92 to 2000-01 (thousands of metric tons)

| State |

1991-92 |

1992-93 |

1993-94 |

1994-95 |

1995-96 |

1996-97 |

1997-98 |

1998-99 |

1999-00 |

2000-01 |

2001-02 |

| Andhra Pradesh |

2943 |

3103 |

3766 |

4221 |

4261 |

4471 |

4473 |

4842 |

4730 |

4904 |

5145 |

| Arunachal

Pradesh |

7 |

21 |

21 |

22 |

42 |

44 |

43 |

45 |

45 |

45.5 |

55 |

| Assam |

639 |

658 |

676 |

698 |

699 |

714 |

719 |

725 |

822 |

852 |

894 |

| Bihar |

3210 |

3195 |

3215 |

3250 |

3321 |

3410 |

3420 |

3440 |

3740 |

3878 |

4068 |

| Chandigarh |

34 |

37 |

38 |

39 |

41 |

42 |

43 |

43 |

42 |

44 |

46 |

| Dadra and

Nagar Haveli |

3 |

10 |

7 |

8 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

1 |

| Daman and

Diu |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

|

| Delhi |

227 |

235 |

252 |

257 |

261 |

264 |

267 |

290 |

295 |

306 |

321 |

| Goa |

28 |

30 |

33 |

36 |

37 |

37 |

38 |

41 |

43 |

45 |

47 |

| Gujarat |

3591 |

3795 |

3935 |

4459 |

4608 |

4831 |

4913 |

5059 |

5124 |

5313 |

5573 |

| Haryana |

3565 |

3715 |

3850 |

4062 |

4055 |

4204 |

4373 |

4527 |

4673 |

4845 |

4976 |

| Himachal

Pradesh |

597 |

610 |

654 |

663 |

676 |

698 |

714 |

724 |

745 |

772 |

810 |

| Jammu and

Kashmir |

515 |

937 |

780 |

641 |

869 |

992 |

979 |

990 |

1000 |

1037 |

1088 |

| Karnataka |

2475 |

2590 |

2736 |

3003 |

3190 |

3460 |

3970 |

4231 |

4925 |

5106 |

5357 |

| Kerala |

1785 |

1889 |

2001 |

2118 |

2192 |

2258 |

2343 |

2420 |

2673 |

2771 |

2907 |

| Lakshadweep |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Madhya

Pradesh |

4806 |

4879 |

4975 |

5047 |

5125 |

5224 |

5377 |

5442 |

5600 |

5806 |

6091 |

| Maharashtra |

3955 |

4102 |

4250 |

4812 |

4991 |

5127 |

5193 |

5609 |

5810 |

5850 |

6024 |

| Manipur |

83 |

83 |

84 |

64 |

57 |

61 |

62 |

65 |

67 |

69 |

73 |

| Meghalaya |

50 |

52 |

53 |

54 |

57 |

58 |

59 |

61 |

65 |

67 |

71 |

| Mizoram |

8 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

17 |

20 |

10 |

10 |

11 |

| Nagaland |

43 |

44 |

45 |

43 |

44 |

46 |

46 |

47.5 |

49.5 |

51 |

54 |

| Orissa |

505 |

542 |

565 |

584 |

648 |

687 |

672 |

733 |

795 |

824 |

865 |

| Pondichery |

27 |

27 |

32 |

33 |

33 |

38 |

36 |

36 |

35 |

36 |

38 |

| Punjab |

5382 |

5583 |

5970 |

6215 |

6424 |

6755 |

7165 |

7394 |

7700 |

7984 |

8375 |

| Rajasthan |

4474 |

4586 |

4958 |

5103 |

5449 |

5874 |

6487 |

6923 |

5820 |

6034 |

6330 |

| Sikkim |

29 |

30 |

30 |

32 |

33 |

34 |

35 |

34.5 |

43 |

44 |

46 |

| Tamil Nadu |

3357 |

3468 |

3524 |

3695 |

3791 |

3976 |

4061 |

4273 |

4256 |

4413 |

4629 |

| Tripura |

32 |

34 |

35 |

38 |

39 |

44 |

57 |

76 |

49 |

51 |

53 |

| Uttar

Pradesh |

10206 |

10649 |

10991 |

11321 |

11878 |

12387 |

12934 |

13618 |

15176 |

15735 |

16506 |

| West

Bengal |

3019 |

3023 |

3095 |

3250 |

3341 |

3376 |

3415 |

3441 |

3750 |

3888 |

4079 |

| India |

55620 |

57962 |

60607 |

63804 |

66198 |

69147 |

71940 |

75182 |

78117 |

80817 |

84570 |

Source:

NDDB, 2003.

Annex Table 2.3 Per capita availability of milk in major states and union territories in India: 1991-92 to 2000-01 (gram/day)

Annex Table 2.3 Per capita availability of milk in major states and union territories in India: 1991-92 to 2000-01 (gram/day)

| State |

1991-92

|

1992-93

|

1993-94

|

1994-95

|

1995-96

|

1996-97

|

1997-98

|

1998-99

|

1999-00

|

2000-01

|

| Andhra

Pradesh |

121

|

126

|

151

|

167

|

167

|

173

|

170

|

182

|

186

|

189

|

| Arunachal

Pradesh |

22

|

65

|

64

|

65

|

121

|

124

|

119

|

121

|

118

|

117

|

| Assam |

78

|

79

|

80

|

81

|

80

|

80

|

79

|

79

|

88

|

89

|

| Bihar |

102

|

99

|

97

|

96

|

96

|

96

|

94

|

92

|

98

|

99

|

| Chandigarh |

145

|

153

|

152

|

150

|

153

|

151

|

150

|

145

|

137

|

138

|

| Dadra and

Nagar Haveli |

59

|

189

|

126

|

138

|

82

|

63

|

60

|

114

|

136

|

130

|

| Daman and